Welcome to

Discovering the Whitelaws

of Scotland and the World

Discovering the Whitelaws

of Scotland and the World

About this Website

This website is intended to share information about those who have inherited the Whitelaw name. It includes most of the content of the book ‘Discovering the Whitelaws’ complied by Peter Whitelaw (with Marg Delane) in 2020.

The source book for parts of the early history is ‘The House of Whitelaw’ written by H. Vincent Whitelaw in 1928. Registered members can request a PDF copy by email to peter@peterwhitelaw.com.au

Preface

This book is a project that has taken some 20 years of intermittent research and, as I rapidly approach an ancient age, I thought it was timely to complete it. As an elder in our family lineage I seemed to have become the willing repository for much of this historic material. Like many people I kept putting off the task of transforming it into a relevant history. Part of my reticence was the time needed to do it properly and also a sense of foreboding that the end result would be just another boring family history book. These two things have changed. Firstly, I find that in semi-retirement I now have the time available. And secondly, I have learned a lot more about storytelling while practising the craft of writing.

The approach I have taken is to write a series of short biographies about individual Whitelaws who have piqued my interest. This means that, in the correct definition of a ‘family history’, this book fails because it does not record all of the known facts about every descendant over multiple generations. That’s why I’ve titled the book ‘Discovering the Whitelaws’, not ‘The History of the Whitelaws’. I also realised that the classical family tree expands with geometric progression. It was not uncommon for couples to produce 11 or 12 children and any attempt to track their individual histories can rapidly become tangential to the main story and very time consuming. It also makes for a very large family tree diagram. Therefore, I have restricted my journey of discovery to my paternal ancestors and their offspring and a few other interesting characters. This approach has enabled me to include smaller family trees relevant to the individuals researched.

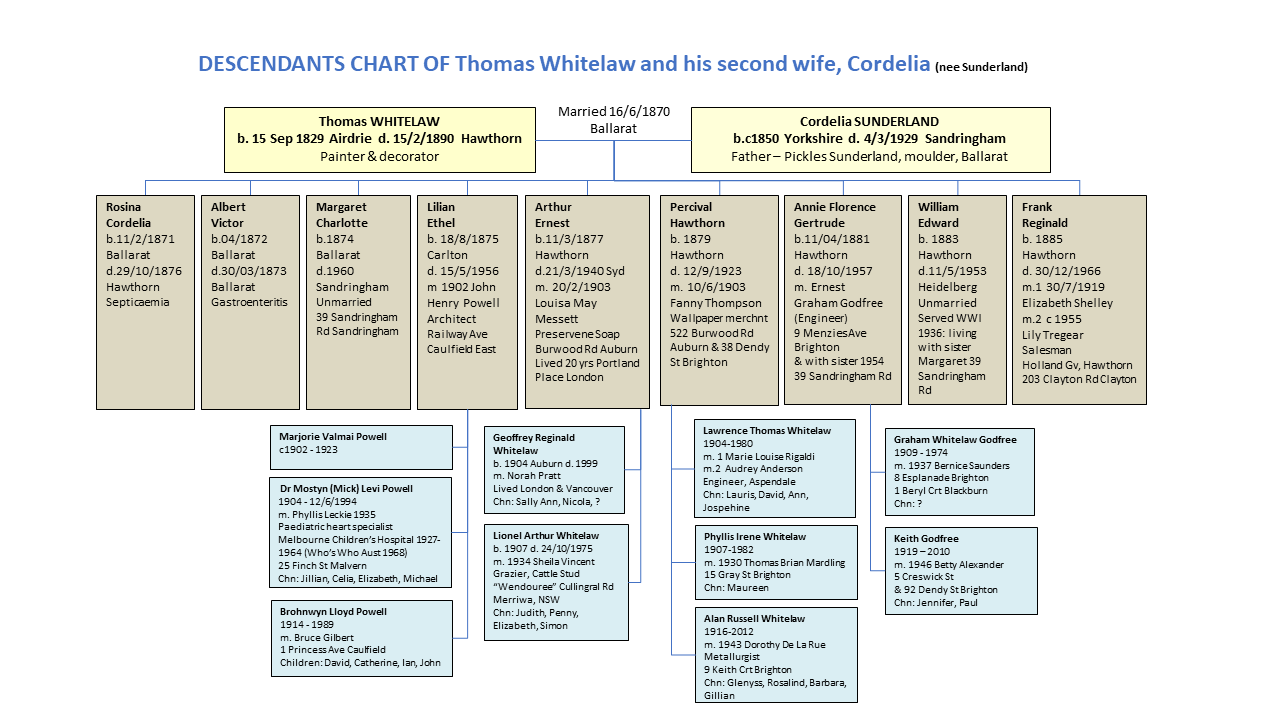

I need to recognise a primary source for this book as ‘The House of Whitelaw’ by H. Vincent Whitelaw published in 1928. I also acknowledge the extensive research conducted by my cousin Margaret Delane, her mother Beatrice (Betty) Fitzgerald, (nee Whitelaw) and our grandmother Evelyn Agnes Linda Whitelaw (nee Munro). Margaret has researched and written most of the chapters on the Ballarat Whitelaws, Thomas and Henry Albert.

In an endeavour to make the individual stories interesting we have included some contextual information about where the characters lived, what it was like living in those times, how they lived and what they may have experienced during their lives. This approach occasionally verges on creative non-fiction and may not be totally accurate, but I trust it is more engaging. I should state that we have verified the facts as much as we can, so the narrative should be believable.

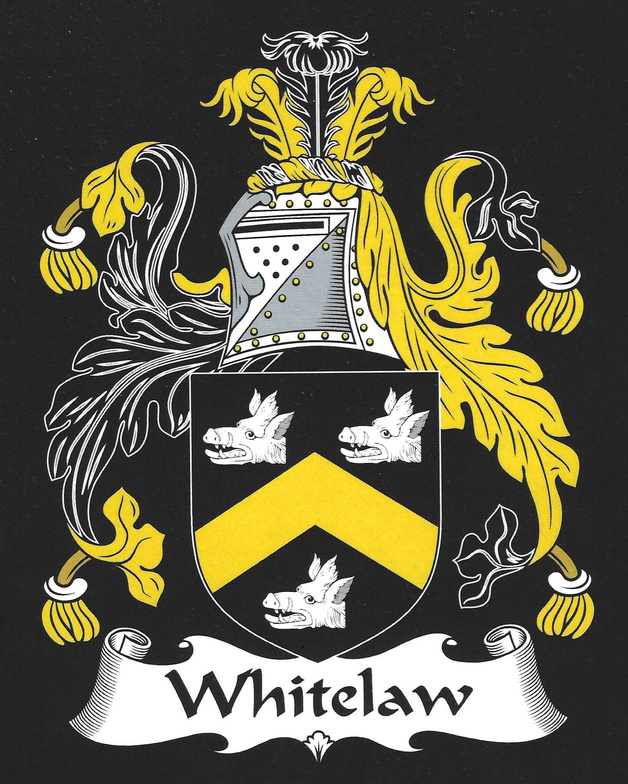

A key element in any story is the ‘theme’. As I researched the people, I began to realise how committed and tenacious many of our ancestors must have been to survive in difficult times and to achieve what they did. I then linked this Whitelaw trait to the Latin motto that appears on our coat of arms ‘Gradatim Plena’ which can be translated as ‘gradual completion’ or ‘full by degrees’. It reflects the dogged persistence that I suspect many of us have inherited.

Why did I write this book? Apart from a feeling of obligation to families and our ancestors, I have found some of the stories fascinating. I think it is incredible that we can track back reliably 487 years (and possibly 620 years) of Whitelaw ancestors and, to some extent, relive what some of them experienced. I remain hopeful that the children of our current generation, our grandchildren and their children will learn about and appreciate their heritage.

Peter Roy Whitelaw 2020

About Scotland

The country of Scotland is the northern-most part of the United Kingdom. It has a 154 km land border with England, and it is surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, the North Sea to the north-east and the Irish Sea to the south.

It is 78,000 square kilometres in area. Scotland has a current population of 5.5 million. The northern half of Scotland is mountainous and known as the ‘highlands’, the flatter southern area is known as the ‘lowlands’. There are also about 790 islands and about 30,000 lochs (lakes) within Scotland

The lowlands are known for their fertile farmland and thick woodlands, the Highlands for their towering mountains, sweeping moorland and deep lochs, and the islands for their compact wild landscapes, beautiful beaches and far-reaching sea views.

Hence, it became much more practical to travel on the high ground (the 'High Way') where one could avoid the mud and the robbers. These roads (or rather tracks) became known as the King's Highway.

Airdrie really came to prominence through its weaving industry. Airdrie Weavers Society was founded in 1781 and flax was being grown in sixteen farms in and around the burgh. In the last decade of the eighteenth century, coal mining was in progress and around thirty collieries were employed. Weaving continued to flourish making up a substantial part of the population of over 2,500 around the turn of the 19th century.

Linen is a textile made from the fibres of the flax plant (also known as linseed). Linen is very strong and absorbent and dries faster than cotton. Because of these characteristics, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments.

At first the flax was grown, dressed, spun, and woven by the people for their own use; but towards the close of the sixteenth century linen goods formed the chief part of the exports from Scotland to foreign countries. A considerable quantity of Scotch linen found its way into England.

The linen manufacturers of Scotland derived great advantage from the union with England. The duties charged on goods exported to the sister kingdom were removed, and at the same time the colonies were opened to Scottish enterprise. A period of great industrial activity set in, and the quantity of linen goods produced was much increased.

Whitelaws in Scotland

It was in the year 1415 when James I was the powerful King of Scotland that the first evidence of the Whitelaws can be confirmed. The name James Whitelaw appears as a seal attached to that of the Durham charters, a document recording the findings of a jury.

The name is most commonly spelt 'Whitelaw' or 'Whitlaw' with variations of Whitla, Whitlay, Whitely, Whytelaw. The older forms of spelling are Quhitelaw or Quhytelaw.

In the past it was normal to give a person a Christian name and refer to them as 'of' their property name. Therefore, James Whitelaw was in fact 'James of Whitelaw' referring to the estate of 'Whitelaw' in East Lothian (Haddingtonshire) 28 Km east of Edinburgh. 'White Law' means 'the white or sunny hill'.

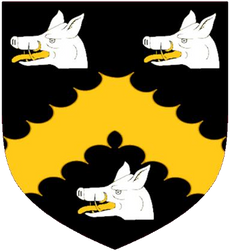

There is evidence based upon a common 'coats of arms' that the family of Whitelaw and the family of Swinton have originally come from a common ancestor.

Before the year 1100 Edulf Swinton, Vicomes of Northumbria was the earliest recorded Scottish landowner. He had a son Liulf. In 1153 Ernulf, the son of Liulf was granted the lands of Swinton by King David I. A later descendant of the Swinton family was Sir John Swinton 13th of that Ilk (of that ilk means John was from the place named Swinton).

King Robert the Bruce (Robert I, 1274-1329) had a daughter Marjory Bruce (born in 1293) who married a Walter Stewart. His name was derived from a long line of ‘stewards’, who were officers that managed the domestic affairs of the royal households. One of their children, born in 1371 became the next king as Robert II. He was known as the First Sovereign of the House of Stewart (later changing to ‘Stuart’).

King Robert II married at least twice and one of his many children was Lady Margaret Stewart who married James, the sixth son of Sir John Swinton. James was granted the estate of 'Whitelaw' and therefore became James of that Ilk (the first recorded Whitelaw).

The clear connection between The Swinton and the Whitelaw name is evident in the identical boars’ heads and yellow chevron that appear on both the Swinton and Whitelaw coats of arms.

Many families in Scotland were granted the right to display a crest or emblem on their armour and other things such as a wax seal used to sign documents. The use of these armorial bearings is called heraldry.

The Swinton family coat of arms dates back as far as 1153. The Whitelaw coat of arms is described as ‘on a helmet befitting his degree is a wreath surmounted by his crest, a black field charged with a gold chevron between three silver boars' heads erased (the necks terminate in three points) below a silver crescent, with an escrole bearing the motto ‘Gradatim Plena’. Several variations have been found with notable changes being the replacement of the crescent with 'a naturally coloured bee placed vertically', the boars' heads being couped (severed), and the inclusion of a fleur-de-lis on the chevron (meaning sixth son).

Discovering the Whitelaws – The Whitelaws of Gartshore 1746 - 1999

Chapter 13 – The Whitelaws of Gartshore 1746 - 1999

Prelude

We had been aware of Sir William Whitelaw MP (1918 – 1999) for many years because of our shared surname. I had purchased his autobiography many

years ago (The Whitelaw Memoirs, 1989) but because he was born in Nairn in Scotland (north-east of Inverness), we saw no visible connection to our family.

There were and are many Whitelaws in, and from Scotland, that may or may not be connected.

William Whitelaw’s Coat of Arms

However, one of our relatives suggested that there might be a link, and I commenced some further research. What I

discovered are two pieces of evidence that suggest we can claim a connection, although, like the vague link we have to the

first known Whitelaw (James c1400), there is no proof that we are directly related to the Whitelaws of Gartshore. They

were known to be Covenanters and the earliest (William) lived in Bothwell, so there is a reasonable probability they were

related.

The first clue was the coat of arms – Sir William Whitelaw’s and ours are virtually identical and it is reported that there is an

identical coat of arms plaque in the old stables (now residences) at the Gartshore Estate. The second clue is that Sir

William’s grandfather, denoted William(4) below, would appear to have been William Whitelaw of ‘Monkland, Nairn and

Midlothian’ (1868 – 1946) who is documented in our primary source ‘The House of Whitelaw’ by H. Vincent Whitelaw

(1928). With that evidence I have made the decision to add this supplementary chapter to the book.

William(1) Whitelaw (m. c1746)

William Whitelaw of Burnhead, Bothwell parish, Lanarkshire, Scotland, was born in 1715, and died in October 1787. He was an extensive farmer, holding

several ‘tacks’, as leased farms were called in Scotland. His letters indicate a man of good education, and excellent business judgment.

In about 1746 he married Marion Hamilton (born at Bothwellhaugh, Bothwell parish, in 1726 and died in 1773.) They moved to Whiteinch about 6km west

of Glasgow (approx. 25km from Gartshore). John Whitelaw, brother of William, lived to the great age of 106 years, walking ten miles to a funeral the week

before his death.

The children of William and Marion were - James, William, George, Thomas, Jean, Alexander, Marion and Janet. Jean married George Jackson. Thomas

married Isabel Cross in February 1786. The eldest, James, a land surveyor, moved to America and joined the colonist army where he rose to the rank of

General. He also became Surveyor-General for the State of Vermont and founded the town of Reigate, Vermont (now spelt Ryegate) which is north of

Boston and just south of Montreal Canada. See James’ story below.

1